Cancer in dogs

Overview

- There are many different types of cancer that can affect dogs, some more serious than others.

- It can be extremely worrying if your dog is diagnosed with cancer but it’s important to remember that not all cancers mean your dog is going to die.

- This articles gives an overview of the types of cancers dogs can get, how they are diagnosed and treated, as well as some questions to ask your vet if your dog is diagnosed.

General information

Cancer is when a cell inside the body multiplies uncontrollably, with no purpose. Most cancers (except certain types of blood cancer), cause tumours to develop, which spread around the body damaging important structures.

There are many different types of cancer, some more serious than others. Some can be seen from the outside (such as skin cancer and mammary cancer), and others can’t (such as liver and lung cancer). It’s important to remember that not all tumours are cancerous (malignant), some are benign.

- Malignant tumours - are cancerous, grow quickly and tend to spread around the body causing problems.

- Benign tumours - are not cancerous, are usually slow growing and don’t tend to spread around the body. Benign tumours only usually cause problems if they get in the way of other body parts (e.g. a big benign lump next to a leg might get in the way and cause pain when your dog is walking).

Types of cancer

Some of the common types of cancers that affect dogs include:

- Skin cancer

- Eyelid cancer

- Cancer of the uterus

- Mammary (breast) cancer

- Testicular cancer

- Anal (bottom) cancer

- Lung cancer

- Abdominal cancers such as:

- Liver cancer

- Kidney cancer

- Stomach cancer

- Ovary cancer

- Bone cancer

- Brain or spinal cancers

- Immune system cancers such as

Diagnosis

It’s rare to be able to tell what a lump is just by looking at it, so your vet may need to run some tests to diagnose it. These tests may include:

Sampling the lump

- Your vet may need to collect some cells from the lump

- This can be done one of three ways:

- ‘Fine needle aspirate’ - take a sample of cells using a needle and syringe (doesn’t often require an anaesthetic).

- ‘Biopsy’ - taking a section of the lump whilst under anaesthetic.

- Removing the lump - surgically removing the whole lump to send it off for analysis.

- Your vet may also need to take samples from other areas of the body (such as lymph nodes/glands) to check for spread.

Diagnostic imaging

- Imaging such as x-rays, ultrasound, MRI and CT scans can help find cancer inside the body.

- Your dog may need to go to a specialist hospital for imaging.

Bloods tests

- There is no specific blood test to check for cancer, but your vet may want to check your dog’s blood for tell tale signs.

Treatment

Your dog’s treatment options will depend on the type of cancer they have, whether it has spread, and their overall health. Follow the links above for information on treatment for the specific type of cancer your dog has (if there is no link yet, please bear with us, we are adding new articles all the time). Common cancer treatments include:

Surgery

- To remove the tumour, or reduce its size.

- Surgery might be the best option to try to stop your dog’s cancer spreading to other parts of their body or to keep your dog comfortable if the lump is causing them pain.

- If a lump’s position or size makes it difficult to remove, your vet may discuss treatment at a specialist veterinary hospital.

- In some cases, surgery is not be the best option and medication may be recommended first, especially if the lump is very large or infected.

Chemotherapy

- Chemotherapy drugs are a group of medications used to kill cancer cells or slow their growth.

- It’s usually given to pets at much lower doses than in humans, to reduce the chance of side effects.

- There are many different types of chemotherapy, some need to be given in a hospital under close supervision and some can be given at home.

- In some cases, chemotherapy is used to control the symptoms of a cancer, meaning the aim is not to get rid of it, but to keep your dog well for as long as possible.

Radiotherapy

- Radiotherapy is a treatment that kills cancer cells with radiation. It is currently only available at a few specialist veterinary hospitals in the UK.

Other medications

- Your vet may recommend medications such as anti-sickness and pain relief to keep your dog comfortable.

Palliative care for incurable cancer

If your dog has a cancer that can’t be cured, there may be certain things that you can do to improve their quality of life and keep them comfortable (known as palliative care). Palliative care usually includes pain relief, special home care and regular check-ups with your vet. If your dog is receiving palliative care but they seem to be getting worse or you’re worried they’re suffering, it’s may be kindest to consider putting them to sleep.

Decision making and questions to ask your vet

Many owners find it extremely difficult to make decisions about their dog’s cancer. Having an open, honest discussion with your vet will help you to understand your dog’s condition and make the best decisions for them. Some helpful questions to ask include:

- What type of cancer does my dog have?

- What are their treatment options?

- Does my dog need referral to a specialist for their treatment?

- How much is treatment likely to cost?

- What is their outlook?

- What are the side effects of treatment?

- How is the treatment given and how often will my dog need to be checked?

It’s important to remember that your vet might not be able to answer all your questions straight away and that there might not be a clear answer (especially about your dog’s outlook/prognosis). The most important thing is to keep your dog’s best interests at heart when making decisions about what tests to run and what treatment to give. It’s important to speak openly with your vet to your vet about your options, finances and what you think is right for your dog.

When it's time to say goodbye

‘When’s the right time to let my dog go?’ - vets are asked this question a lot, and the answer is always different for every dog. When making this difficult decision, the most important thing to consider is your dog’s quality of life. Below are a few things you might want to think about:

- Do they have more bad days than good? (you might want to keep a record)

- Are they enjoying their food?

- Are they enjoying their normal routines such as playing and walks?

- Are they comfortable while they’re sleeping?

- Can they be cured or are they likely to get worse?

- Are there side effects of their treatment or medications?

- Do they become distressed by vet visits?

- Are they becoming distressed or confused? (for example, do they get upset if they toilet in the wrong place? Are they worried by being left alone?)

Your vet will help you make this difficult decision, always speak to your vet openly and honestly about your dog’s quality of life and how you are feeling. As hard as the decision may be, if your dog is suffering, it’s kindest to let them go.

Cost

Treatment costs for cancer can mount into thousands of pounds. It’s important to speak openly to your vet about your finances, the cost of treatment, as well as what you think is right for your dog. There are often several treatment options so if one doesn’t work for you and your pet then the vet may be able to offer another.

When you welcome a new dog into your life, consider getting dog insurance straight away before any signs of illness start. This will give you peace of mind that you have some financial support if they ever get sick.

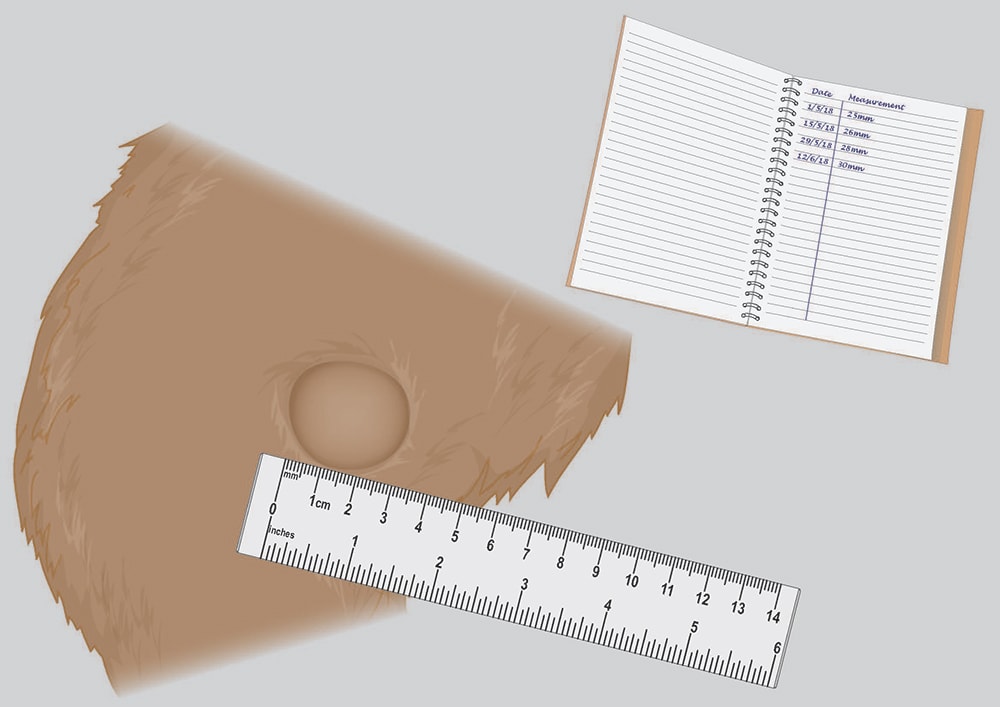

Monitoring lumps

If your vet asks you to monitor your dog’s lump, it’s a good idea to take photographs and measure it every couple of weeks to help you notice if it’s growing or changing. Keep a note of the following:

- Its size

- Its texture (smooth or knobbly)

- Its consistency (hard or soft)

- Whether it’s causing pain

- If it’s bleeding or weeping

Published: September 2020

Did you find this page useful?

Tell us more

Please note, our vets and nurses are unable to respond to questions via this form. If you are concerned about your pet’s health, please contact your vet directly.

Thank you for your feedback

Want to hear more about PDSA and get pet care tips from our vet experts?

Sign up to our e-newsletter

Written by vets and vet nurses. This advice is for UK pets only. Illustrations by Samantha Elmhurst.